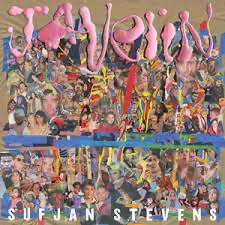

‘Javelin’ is Sufjan Stevens’ latest brutal triumph

Sufjan Stevens’ 10th studio album, “Javelin,” musically feels like a breath of fresh air and emotionally feels as if someone is stomping on your chest.

The technically impressive album has 10 tracks and totals 42 minutes. Released on Oct. 6, it explores themes of love and loss in dazzlingly beautiful noise.

Stevens’ work cannot easily be pigeonholed. His discography includes Christmas albums, an electronic album, a cinematic score, two separate albums named after states and numerous collaborations. In 2018, he received a Grammy nomination in the category "Best Song Written for Visual Media for the hit “Mystery of Love” from the “Call Me by Your Name” soundtrack. His work has always had a celestial quality, and “Javelin” is no different. Featuring a plethora of backup harmonies, rich instrumentals and his strained, hushed voice, it is a nuanced glimpse into his psyche.

One of the three singles and the second song on the album, “A Running Start,” is an immediate standout. Its unique 5/4 time signature gives it a sense of motion, and the lyrics tell a story of him imagining that he’s running away with a lover. (“You throw your arms around my heart / As if to say you’re all I need.”) With references to nature, homey guitar playing and a gorgeous piano melody at the end, it feels like warm sunshine on your face.

At the same time, the song has a tragic quality to it considering it is part of an album dedicated to his partner Evans Richardson, who died in April. Stevens’ dedication to his partner is operatively his coming out, and his grief adds another shade to the album.

The first track, “Goodbye Evergreen,” is an unflinching and uncomfortable exploration of his grief. Its cacophony of instruments and seemingly clashing melodies reflect the disorganization of loss, echoed by the earnest lyrics (“Goodbye, Evergreen / You know I love you / But everything heaven sent / Must burn out in the end”).

“Shit Talk” explores the brutality of a breakup and the guilt associated with fighting and falling out of love. In eight minutes it transitions from softer acoustic sections with timpani drums and choral swells all with various voices calling out “I will always love you” and “I don’t wanna fight at all.” The length is not unusual for Stevens, and he weaves in and out of melodies with ease. The 5/4 time signature leaves the listener imploring for a proper, even end to a musical phrase that never arrives, which brilliantly corresponds to the relationship in the song that never reaches closure.

Stevens’ artistry really shines in its simplicity, as demonstrated by the title track “Javelin (To Have and To Hold)" and “My Red Little Fox.” “Javelin” tells the simple story of his feeling relieved that he didn’t hit someone with a literal javelin, and “My Red Little Fox,” though it is unclear what the little fox is, is a feat in its lyricism alone (“Kiss me like the wind / That flows within your veins”). Coupled with a stripped-down approach featuring his voice, a guitar and minimal backing vocals, both are reprieves from the intense emotion and walls of sounds created by the rest of the album.

Stevens’ deeply personal yet ambiguous songwriting elicits reflection in its listeners. When he asks, in a partial whisper, “Will anybody ever love me?” you can’t help but think the same thing. He comes across as overly fragile and guilt-ridden, especially in “Javelin (To Have and To Hold),” where he fears accidentally injuring a loved one (“It’s a terrible thought / To have and hold”) and “Everything that Rises,” a reflection of guilt and growth ripe with biblical references (“Turn yourself away / From the wickedness I said”).

For those unfamiliar with Stevens’ work, the album may be harder to digest at first. The first track “Goodbye Evergreen,” while a brilliant depiction of his grief, could sound to some listeners as disjointed and atypical clashing noises. The structural brilliance and poetic lyrics are only revealed after subsequent listens. Additionally, the intentional vagueness in his lyricism can be difficult to understand the first time around and may not resonate until the listener really unpacks his themes and stylistic choices.

The final track on the album is his cover of Neil Young’s “There’s A World” where he takes a more subdued and acoustic approach to the song. It is an emotional band-aid on the bullet wound of an album and provides a sense of hope and optimism for the listener.

Post a comment